Truth and justice require calm, and yet

Andrew & Steven. Une Femme Est Une Femme. Grey Belt. ABHOBC: Strip. APB: Transformer. ADVERTISEMENT. NOW 17. To Live and Think Like Pigs.

ITEM

Andrew and Steven, Those Amusing Brothers

ITEM

Une Femme Est Une Femme (Jean-Luc Godard, Anna Karina, 1961)

Self-conscious from the first time the soundtrack cuts out, but this isn't the flare of the tired showman who wants you to feel easy with an old trick - the "well that just happened!" worldview, tediously masculine, a line of arseholes clenched to stop so much as a breeze from getting by.

Soundtrack blaring.

Street noise.

There are literal nods to the camera, sure - "And off she goes" - but Anna Karina's outfit does change when she steps through the peepshow curtain, eh? The joy and the horror here, or perhaps the comedy and the tragedy, comes from the knowledge that this arbitrary nonsense is deeply felt. Worse still, that it’s no easier for us to escape than it is for the goldfish to commit to dry January.

More soundtrack.

Singing. Her voice echoing around an otherwise quiet room full of people who have paid to gawp.

The story is a three-way farce played out using scraps of available material. "Longing for a baby, a stripper pursues another man in order to make her boyfriend jealous” is both a dumb, sexist premise and a burlesque of the same.

Something to the method though. Saying you’re sure you’re in love but unsure of the person you’re in love with gets a laugh, as it should. But the feeling of walking out into the world with love theme blaring, only for reality to meet you with questions or worse, indifference? Too real.

A choreographed argument between two lovers conducted using the words on book covers.

Passing eyes that seem to leer until someone asks them to participate, at which point they look for an exit.

The dream of a total union persists despite its improbability, the preceding action a dance, a modern rite to make the mutual will-to-posses appear fashionable again.

ITEM

Grey Belt

Millennium Grey is psychogeography’s anti-matter: the house style of managed transformation, the digital non-colour of regeneration brochures, masterplans, and Section 106 promises. Millennium Grey is an internet-enabled flattening of the built environment, the final herald of city life shifting from production to consumption, a wipe-clean aesthetic for mobile living: airports, serviced apartments, co-working spaces, UberX cars. Millennium Grey sweeps over walls, floors and ceilings, erasing grit and history, making places too bland for any ghost to haunt.

The ‘Grey Belt’ is Millennium Grey hardened into policy. The British government’s newly coined term for “wastelands and old car parks on the greenbelt,” has been identified as the land upon which we can build new homes - 1.5 million of them. These wastelands are psychogeography’s most valuable real estate, the edgelands, the brambly scrub, the scrap yards, the abandoned lots of Ian Sinclair’s Orbital and Patrick Keiller’s London. Labour says these sites shouldn’t be ‘given the same protections in national policy as rolling hills and nature spots.’

You might argue that this is a 20th century condition we’ve long been familiar with. But the Grey Belt is something new, surpassing the fatalistic capitalism of, say, JG Ballard’s Kingdom Come or Alan Moore’s Big Numbers. In both, shopping centres flatten suburban life into spectacle, absorbing civic space and commodifying desire, but they remain unstable, still shaped by their edgelands substrate, which leaks unpredictably. Entropy persists.

The Grey Belt, by contrast, is deliberate, evicting all ghosts before new foundations are poured. The wastelands, their empty fridges and industrial spills are no longer accidental; they will be measured, classified, packaged for extraction.

In eagerly chasing the Grey Belt dollar, have today’s architects - consumers and champions of 90s psychogeography - misread the warnings of Moore, Ballard, Keiller, and Sinclair as mere mood-board material after all?

ITEM

A Brief History of British Comics

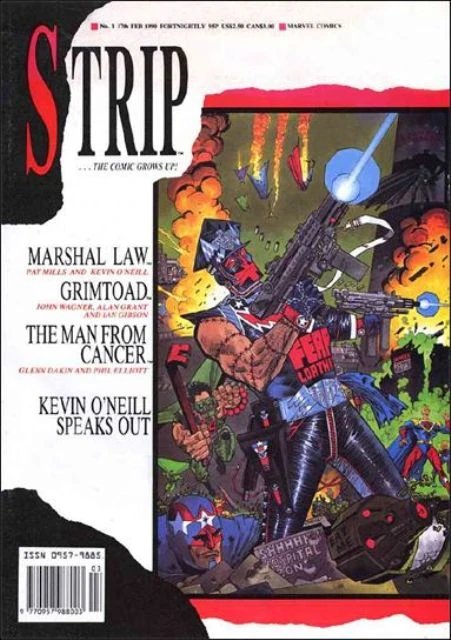

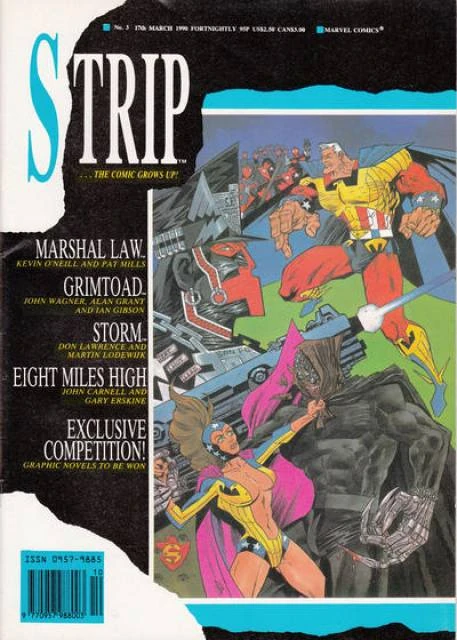

14: STRIP

- Publisher – Marvel UK

- February - November 1990

- 20 issues

We need to talk about ‘Marshal Law’.

There’s never been a comic like it. It’s one of the ugliest, most brutal things to have been conceived in the artform, a howl of despair and anger, mocking with spittle-flecked fury. Two great comics innovators pushing themselves into hysterical contortions, raging against the vanilla conservatism of the form they have slaved over, un-thanked and unrewarded.

Garth Ennis and Mark Millar clearly gazed in wonder at this monstrous comic, but nothing either have done has the unhinged, dangerous quality of Mills and O’Neill’s Gotterdammerung. O’Neill’s usually elegant and playful grotesquery is replaced here with pumped up, plastic-surgery scar reflections of the gross aesthetic vanity of the 1980s. Everything looks painful in ‘Marshal Law’; sex, fighting, clothing, smiling. Mills works himself into a lather, spitting venomous scorn in every direction.

For all its righteous anger, it’s a work that flirts dangerously with misogyny. This is a comic that starts with a vicious rape murder, and it’s an exploitative, punishing depiction.

Incredibly strong stuff that’s lost none of its transgressive power.

The fact that I first encountered it within the wine-bar aspirant chic of Marvel UK’s Strip anthology was even more disorientating.

This sat alongside every other comic in the newsagents. Flicking through, ‘Marshal Law’ terrified me. This was not a comic that my Mum could ever see. As verboten as a porn mag.

Strip was otherwise a puzzling collection of strips, under a faux-mature trade dress. Phill Elliot’s charming ‘Man from Cancer’, Wagner & Grant’s oddball ‘Genghis Grimtoad’, and Don Lawrence’s beautiful but musty ‘Storm’. All of them buffeted into invisibility in ‘Marshal Law’s’ bloody wake.

Gazing now at barren newsagent shelves, we mourn the loss of Strip, even if it was never more than a pretty shell for a rotten, stinking egg.

ITEM

Adventures in Pyramid Building: Transformer

J is putting her dad into the Pyramid but she’s putting them in as Amanda, their other life that was kept locked up and only let out toward the end. Her dad was a photographer and she shows me these amazing pictures. Amanda as Femme Fatal, Amanda as fierce new wave punk girl, Amanda being saucy, Amanda as glamour. A fabulous life lived alongside the everyday.

Last year I met Y he was putting his mum and dad into the pyramid, being cheeky he’d mixed them into one brick. They’d had a passionate relationship, together and apart. Step siblings and half siblings, a family tree like spaghetti thrown at a wall. Here he had a space for him and his parents, something for just the three of them.

There is a transformative effect to the pyramid. It allows people to be their weirder, messier selves, the self that their friends know. It allows the people left behind to set out their relationship to the deceased, and not have to smooth out any of those contradictions that come with us being brilliant difficult people loving brilliant difficult people. You get to go in as the things you chose to be. You get to go in as the bits of you that you had to lop off or smooth out to fit into the world.

The tools of death that we have, the death technology that our society privileges has a tendency to take our amazing, beautiful, angry, dark, sexy lives and squash them into the shape of grey school trousers.

J struggles out of her coats despite the cold. She wants her Peace jumper visible. She walks onstage Brick held high above her while Clare reads a poem J wrote about her dad, Amanda. When the poem is done Daisy ritually cements the brick into the Pyramid while we cheer and clap and play our foghorns. There is a sincerity to the Pyramid that is valuable.

https://www.thepeoplespyramid.org

ITEM

ADVERTISEMENT

ITEM

Find this moment and it multiply

Tell just one person that you liked this newsletter. Word of mouth, more than any other form of promotion, is how creative works get noticed and sustain themselves. Thank you very much for reading.

ITEM

I LEAVE ENCOURAGING COMMENTS ON 26 YEAR OLD ARTISTS YOUTUBES NOW: VERY SEEMLY BEHAVIOUR

Good evening readers, you’re very beautiful tonight - was staggered recently to look at the track listing on my first full album after a spirited discussion on the merits or otherwise of MC Tunes [who is: not on this album] in the Mindless Ones chat. Anyway shouts to the team who compiled NOW 17 - it’s a Marxist truism that we are products of our age and locality, but whilst I merely remembered it as something with one of my least favourite songs by my favourite band in the 1990s Faith No More - adding to a burgeoning fandom sparked by the aptly named EPIC vid on ITV’s Saturday morning chart show (why I am reading the man who plays that moving classic piano outro’s enjoyably lurid (and I think I can say fruity here?) biography right now.)… really, NOW 17 is a large part of my cultural DNA.

Also created a lifelong hatred of young boy sperm injector(/thief?) Cliff Richard, and a mild dislike of reggae, but there’s early British proto-jungle with the Rebel MC, and several techno/electro - frankly, while Blue Savannah is a plainer track Erasure elided into that mode often - artists, including Technotronic… the Dutch were really at it then, bet Amsterdam ‘92 was a scene. You can find FNM interpolating Pump Up the Jam right here from 4:09… ah want a place to stay, leave a comment if you dare tonight. Adamski - Killer… remember Adamski? Bet Seal fucking doesn’t, eh?!

Lot of if we are being completely honest audio drugs here, the Candy Flip Strawberry Fields cover… Everything Starts With An E [including as Patton notes in Brixton ‘Epic’] a document of MDMA’s drift from a manufactured exercise booster to Da Club - I inevitably ended up enjoying ecstasy tablets very much indeed and would probably yet invest in a vat of the stuff and end up emotionally like Swimming Paul. Very cool stuff.

MY SOUL IS FADING, BUT I KNOW WHAT PURE GRACE COULD BE

ITEM

To Live and Think Like Pigs by Gilles Châtelet (translated Robin Mackay, Urbanomic/Sequence, 2014)

It is 30 years since the street drama of 1968, one year left til suicide at 55, cheating AIDS of the stat. Defiant in face of the next plateau, unreachable and worthless, refused.

There is no colder or more functional millennium document, more clear a survey of the future present from that one, we now know, vanishing moment of elevation and perspective. The truth of tomorrow’s today revealed itself first in the bars, floors and balconies of Le Palace, fusions of overpaid pop stars, trade impresarios, manacled academics, animal rights fatales, cocktailed into a vanguard for the nascent knowledge economy. Dancing while projections of Mitterand, Reagan, Thatcher smile approvingly from the years above, feet burning away the remnants of industrial repetitions and certainties, freedoms shimmying into choices.

78, 88, 98. Numbers moving quickly, digital signals crossing the critical line from nothing into something, necessitated by the spatial void created by the energy of their own calculation, pulled into being by the empty vacuum of the future. As the figures threatened to sublime into a run of three zeroes, a trinity of perfect absences, consistent faith in the logics powering them collapsed, and Tiamat resurrected to end an era, 90s style: chaos worship, reverence of catastrophe, structural disorder as norm.

Châtelet looks her in the eye and makes plain the lie and error in the discordian cult’s promise (capital optional) that creation follows destruction. Stochastic uncertainty is an artefact of mathematics, not nature, and numerical randomness is generated by order’s direct command: friction between distinct points brought into relation through human intervention. The fractal creative matrix, pure and fundamental they said, was just graphic design, and the claims made on its behalf for trust in the market’s wheezes and its perfect decisions is produced, iterated and enforced, not spontaneous or indwelling. Marduk the first banker, a primal beast is disemboweled and uncreated in reverse, a nothing forced into being where something was before.