All the winds and the lulls together

A Brief History of British Comics: Revolver. Nuance. Mach Zero Memory. Judge Dredd Annual 1989. Scottish Friction 6: Deep Wheel Orcadia/Archaeologies of the Future. Haunted House. Weird one, but okay. The Sleep of the Great Hypnotist.

ITEM

A Brief History of British Comics

1: REVOLVER

- Publisher: Fleetway Publications

- July 1990 – January 1991

- 7 issues

It was a strange, malformed hybrid from the start, a collection of disparate ideas in search of a unifying concept. A thing that existed on vibe-fumes alone, representative of the ‘anything-goes’ era it sprang from. A curio and an experiment soon to be abandoned.

‘Revolver’ feels like potential. Not necessarily realised and probably hobbled by the publishing model that birthed it, yet there’s something in those scant few issues that is exciting, exotic and strange.

And really, we must marvel, especially in our current arid landscape, at the impertinence of this comic, and other similarly fallen brethren. Sitting on the shelves of high street newsagents, a psychedelic sniper nestled between Take-A-Break and Q Magazine.

The eclecticism always felt a little strained, lacking the genuine freewheeling chaos of ‘Deadline’; Morrison and Hughes’ late-stage revisionist Dan Dare rubbing its brutal, buttoned-up shoulders with the 70s head-shop musk of Charles Shaar Murray’s Hendrix meditation. Milligan and McCarthy’s Rogan Josh is a genuine acid-curdled masterpiece. Despite the unimpeachable cartooning of Steve Parkhouse, Happenstance & Kismet feels teleported from another time and generation.

The design was impeccable, thrillingly modern. The vibrancy of the 80s-90s pivot reflected in Rian Hughes’ bold, bright graphical eye. The title, so achingly prescient in its prediction of the forthcoming 60s nostalgia tsunami. Old and new. A newsprint anthology designed to ensnare unwitting Watchmen alumni and diasporic fashionistas. Fronted by Milligan and Morrison, the fuckable faces of boy’s weeklies.

It arrived with fanfare and money. Tours and swanky launches. Then it was gone, before the decade it anticipated had even got going. Tumbling readerships and a collapsing market.

Those of us who were there to witness it, cherished it. Spoke (speak?) of it in hushed tones – a path not taken, another world. Hidden in the title. ‘Evolve’.

A challenge not met.

ITEM

WHAT SIDE ARE YOU ON? THERE’S A WAR ON! YOU CALL THEM NAZI, THEY CALL YOU PAEDO (SPELT “PEDO”). MAKE SURE YOU’RE ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF HISTORY! UNLOCK YOUR PHONE, ENTER THE BATTLEGROUND AND SAY IT AS LOUD AS YOU CAN!

ITEM

Zero memory

I’m sitting in Boots, it’s May 1978, and I think I just turned six. We’re at the prescription bit, at the back, and there’s a seat, and I’m sitting on it, my mum is standing up – she’s in the queue – and my brother is around too. He’s got Star Lord. Number 3. A Kevin O’Neill cover. A space battle. It looks painted!

But I’ve got 2000AD. Prog 66. I’ll be getting it from now on. Daddy said so. My brother can get Star Lord and I can get 2000AD. Judge Dredd’s on the cover. It’s a Mike McMahon cover. It’s OK. A mutant with a rat on his head is threatening Dredd with a knife, but this actual bit on the cover doesn’t happen in the story. It’s quite annoying. But it's mine. Not my brother’s. And Mach Zero part two is in it.

The cover last week was amazing. Mach Zero smashing his way out of the comic! I think it’s by the Flesh artist, who I really like. He did this great drawing of Claw Carver fighting a sort of small, really vicious T Rex. It’s probably my favourite 2000AD pic so far.

My brother is going on about Strontium Dog and the full-colour artwork by Ezquerra. It does look good. The paper is much glossier than 2000AD. And Ro-Busters is really good too. But I prefer 2000AD. Mainly, this week, because of Mach Zero, who is kind of like the Hulk, but more likeable. I don’t like the Hulk really. I always want the Thing to win the fights. But Mach Zero has a Kermit t-shirt, and I feel sorry for him, and I’m hoping in the story that he kills Sharpe, the man who made the whole Mach programme - Man Activated by Compu-puncture Hyperpower. We’ll see.

ITEM

Judge Dredd Annual 1989

The Judge Dredd Annual 1989 is largely unremarkable, a slight Dredd fighting a Vampire in a decaying seaside town elevated by Ezquerra’s lurid paints, a clutch of Daily Star strips, 84 pages of reprint and a lot of filler. But it’s the filler that makes it one of those artefacts that accidentally captures a moment of movement within the culture.

Released in winter 1988 it’s at the fag-end of the annual Annual tradition. The sales spike of the 70s IPC revolution is a blip in an overall decline from the multi-million circulations of the Eagle and Lion. In the transition from mass audience to niche market the Annuals morph into French-flapped Yearbooks before disappearing altogether in the 90s.

I can’t find circulation figures for Annuals but in ’88/’89 2000ad is shifting 98,000 copies a week and Annuals have multiple audiences, yer actual fans, the ‘I remember that’, and aunties desperate for something for the family weird kid. This is power. Enshrined in adult minds as ‘for kids’, broad reach but too small to notice. The last moral panic Action in ’76. Video nasties, computer games and yer actual Satan have surpassed them.

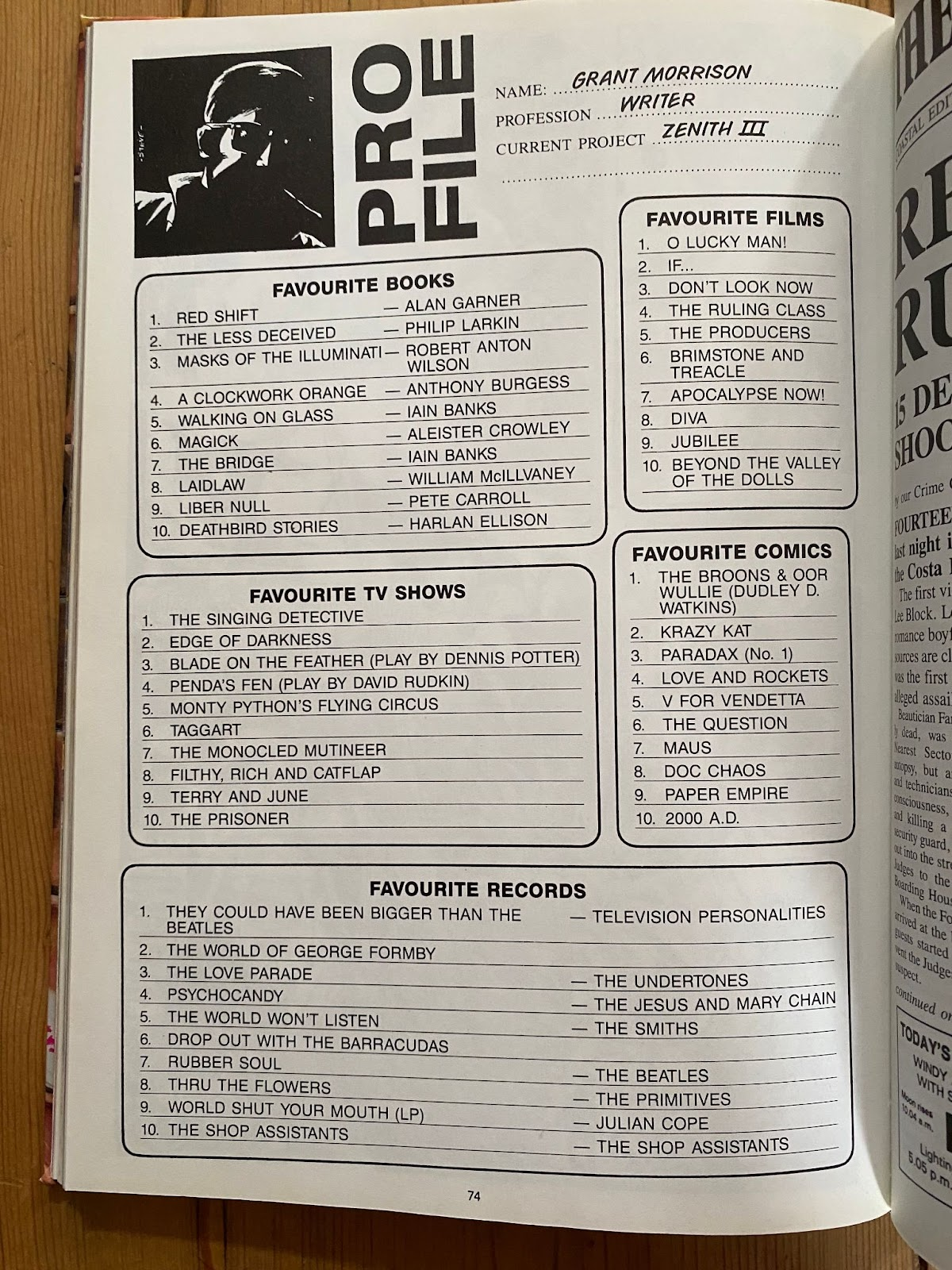

The filler includes creator profiles. John Wagner, Dredd’s co-creator, in the imperial phase for which he still hasn’t had his due, recommends The Sweeny Movie, The Diary of a Nobody and I, Claudius.

Grant Morrison, in 2000ad terms the wunderkind, two series of the electrifying Zenith, recommending Penda’s Fen, Robert Anton Wilson, Magick by Aleister Crowley and Peter Carroll’s Liber Null. Zenith contained traces, the alien forms of the Lloigor taken straight from Brian Ward’s Psychonaut illustrations but that’s a reference for insiders. This is direct. Auntie Brenda and Robert Maxwell in an inadvertent team-up promoting a life of sex magick to the kids on Christmas morning.

ITEM

Thargnote

Tell just one person that you liked this newsletter. Word of mouth, more than any other form of promotion, is how creative works get noticed and sustain themselves. Thank you for reading.

ITEM

Scottish Friction 6: Deep Wheel Orcadia (Harry Josephine Giles, 2021); Archaeologies of the Future (Fredric Jameson, 2005)

Try to remember: there are other ways of telling, other tools to remake the world.

“”The drive maks a pock, see,

o hyperspace tae win trou,

tae exceed relatievistic constraints.””

A shard from Deep Wheel Orcadia, there. Orcadian dialect sci-fi novel, comes with a gloss in English:

“”The drive makes a packetpocket, see, of hyperspace to reachtravelachieve through, to exceed relativistic constraints.””

A lot of cunning work at play in those translations. A slow blooming suggestion that the centre is an illusion maintained by complicity and force. I can hear that boom tube thunder in the space between “pock” and “packetpocket”. This book is portal, an invitation to ask what we’re trying to reachtravelachieve, and from where.

I dream of an escape from the drone of dead stories. Can we speak about gentrification in Glasgow without performing chattering class gossip? Can we talk about “the highlands and islands” without remaking the UK in miniature? Can we end empire without craving a biscuit?

I dream of a country unrecognisable and true – “O my Scots, there is no Scotland!”

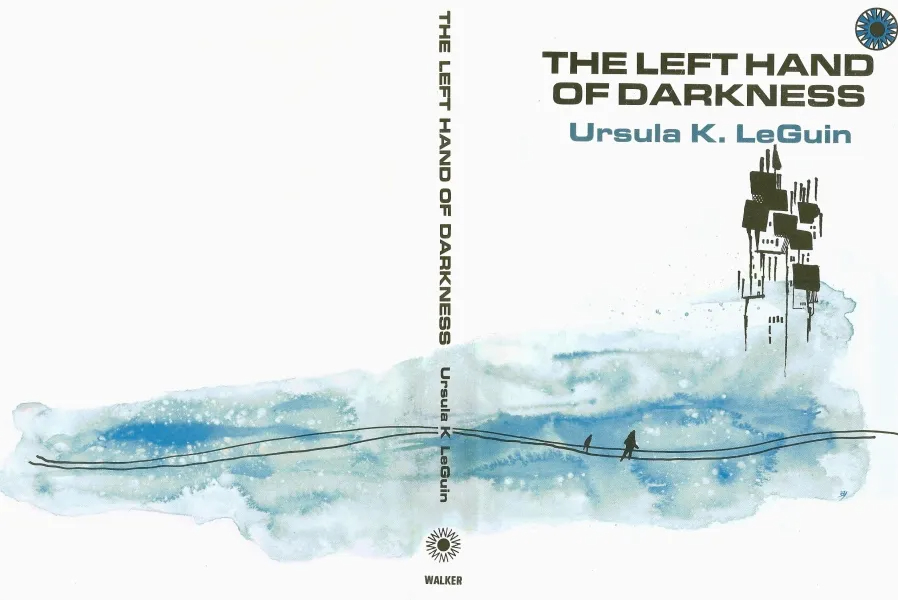

Fredric Jameson on Ursula Le Guin: “such “no-places” offer little more than a breathing space, a momentary relief from the overwhelming presence of late capitalism.” Harvie-Sturgeonism in ruins, Scottish independence currently looks like science fiction. An attempt to exceed constraints reduced to a “no-place”, a brief reprieve.

Jameson again: “In that case, the deepest subject of Le Guin’s Left Hand of Darkness would not be utopia as such, but rather our own incapacity to conceive it in the first place.”

Despite evidence to the contrary, I can’twon’t believe it’s all waste. Like growing a language, unearthing the future is a demand and a joy. And so we return and begin again: “Our victories seem fleeting, sometimes. But so too are our defeats.”

ITEM

Haunted House

I’m somewhat fixated on Jacob Geller’s video essay Control, Anatomy and the Legacy of the Haunted House. Without wishing to regurgitate Geller’s thoughts - after all, you can watch the video - I’ll simply say that he’s concerned with houses that haunt, like the kind found in Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, Mark Z. Danielewski’s The House of Leaves and Remedy Entertainment’s video game Control. Places which unravel into bizarre and terrifying vistas the second they’re unwatched. Beyond his elegant examination of just why this is scary, Geller’s key insight - and here be spoilers - is a kind of reversal of his initial position: ultimately it’s not the house that haunts. It’s us.

This is something like Sartre’s point in his novel Nausea. In moments of estrangement, Sartre’s protagonist discovers that objects — a chestnut root, a pebble, the seat of a train — surge up as radically contingent *things*, bristling with a grotesque excess of being. Estrangement from the home is perhaps the most radical kind. What horrors might be revealed when it is left to its own devices, stripped of relational form and human function?

The crucial move in Geller’s thesis - which he never entirely unpacks - is that man struggles to control an always already weird world, ready to explode into chaos and absurdity. So we adopt ghost-like patterns we call lives, repeated efforts to bring an order that will never come. Looking at the final images he leaves us with, I’d take this further. What if that (e)strangeness is indicative of a kind of phenomenological break? What if we, as peculiar, meaning making things, can never truly touch the-world-in-itself. The powers of the character in Control, such as flight, telekinesis, and the poltergeist-esque violence she brings, are a poetic expression of our unnaturalness and incongruity.

ITEM

WEIRD ONE, BUT OKAY

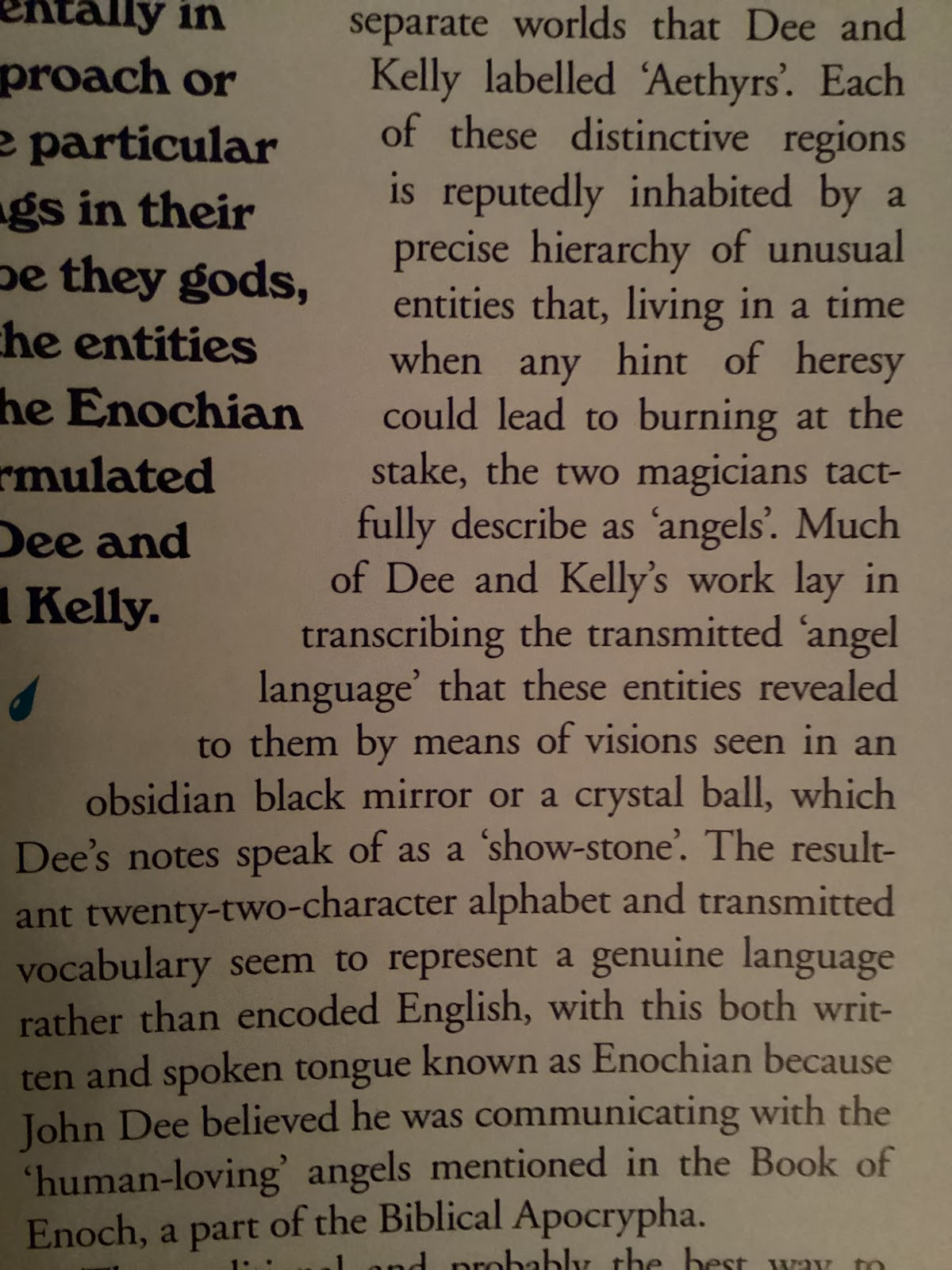

Back on the Alan, back on the Moores, god do you know I might ask for his Maestro BBC class thing for Christmas, why not - anyway another motif I noticed going over continuity here was this, well dually this, the compound concepts of angelic language and I suppose how to orient them (like - “hope” and “disrupt” are multivalent ideas, some good, some really not, anyone over age 23 needs to know this) but the visual motif of the black dot in Doom Patrol or sphere in Akira or circle - it’s all the same in comics, sorry Mr Terrific - and getting inside this node that I am calling the Immobilarity just for the hell of it*. It is also the Phoenix egg in NEWXMEN and the Incal, or half of it anyhoo, in The Incal - I can’t really remember and can’t be arsed checking because Jodorowsky really does have a problem with women, yes I will watch the film about his putative Dune adaptation one day.

Big hero of Kanye West’s as it happens, but at least Kanye loved his mum.

Anyway here it is a ‘show-stone’ to access Enochian language… cor, that worked out pretty neatly eh readers?!

*the rap Vatican bank is open and Clipse are playing the ceremony with John Legend

NEW LOLA YOUNG ON THE STERE-ERE-O FOR DADDY & DAUGHTER DAY

ITEM

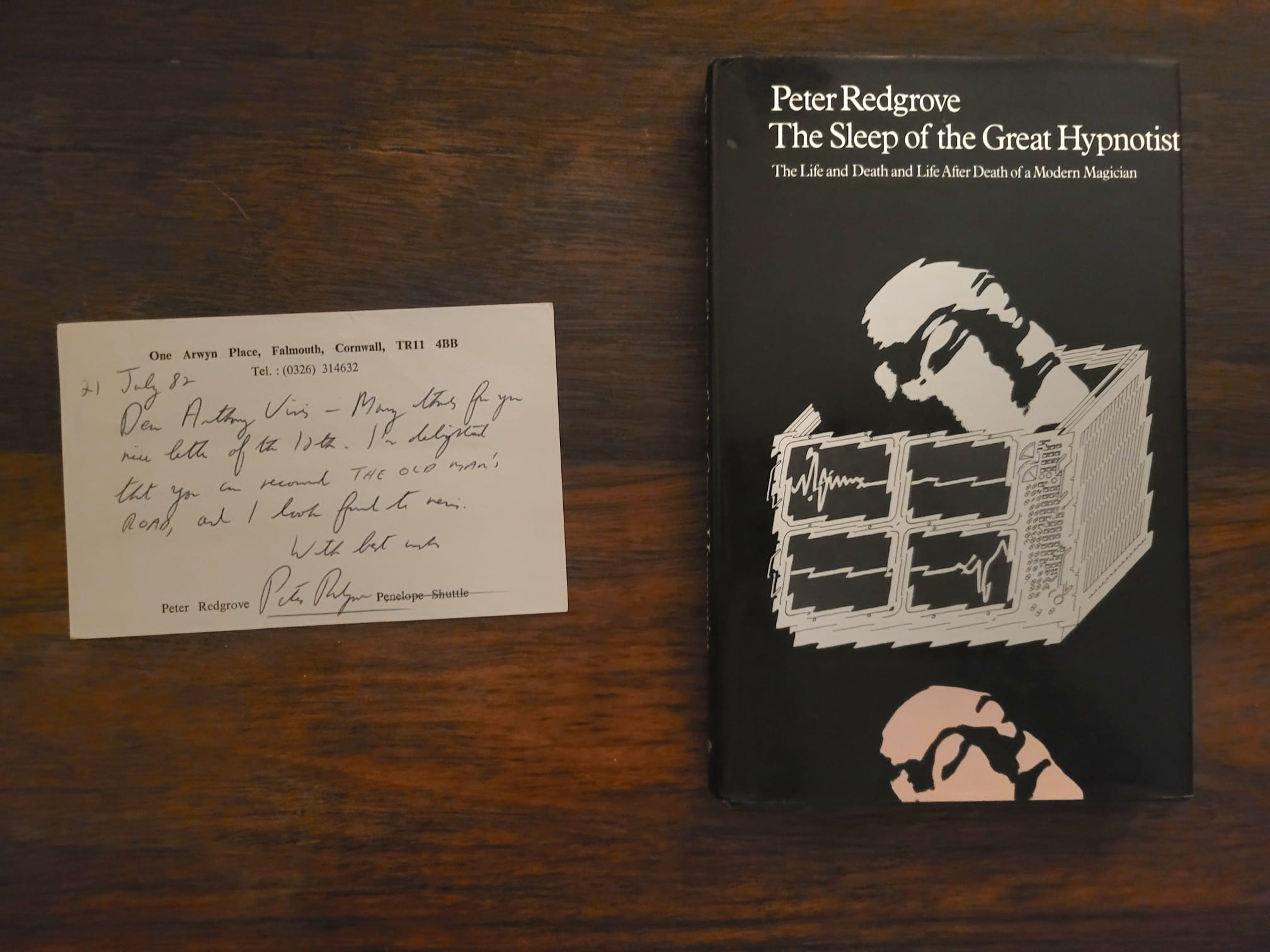

The Sleep of the Great Hypnotist by Peter Redgrove (Routledge & Kegan Hall, 1979)

Hidden English magic masterpiece from the final days before Thacher. Psychedelic modernism still rules the TV age and offers the dream of collective individuation through applied spiritual science. The silver in the chain after John Cowper Powys and Kenneth Grant, Redgrove’s poetic animation smears itself wet and rampant over a novel reworking of the legend of Faust's daughter, her entrapment and inheritance. A doctor of hypnotism working his way through the private sitting rooms, conference halls and TV seances of celebrity mesmerism, who curses his child never to rest until she rescues him from the underworld so he may redeem fallen mankind with good news from beyond.

Bending oscilloscope tech and cathode ray particles to probe distant interior worlds, from fifty years deep Hypnotist reveals the trance of psychological damage our own moment is immersed in. Massive mediation, feedback, instant iterative recursion, the screens inside and outside our nerves reflect each other and generate baroque, possessing fantasies which require simple but forbidden or inaccessible training to channel. Rescue tools from the ontological hijack currently reprogramming reality.

The second half of the story falls onto my lap at about page ten. A postcard July 1982, Redgrove to Anthony Vivis, then BBC commissioning editor of radio drama. A courteous compliment on a recent broadcast of Auden (Past shrines to a cosmological myth/No heretic today would be caught dead with), the enclosed gift a tacit hint between two Cambridge men: Wouldn’t this make a great radio play? Or take it across the hall for Leland or Potter to transmute my advanced critique of TV into TV, close the circuit, sit back and watch the residuals gather?

Judging from the condition of my edition, Vivis never got the memo and the gift went unread. Good poets are graceful, but great poets are petty and cherish good bitterness. Redgrove, the same year:

Broadcasting House

Is a ghost-station, its interior pitchy-dark

As a radio-set’s inside, everything there

Has been turned into invisible wavelengths